Letters to Peregrinus #25 - On the Fact of a Face

Dear Peregrinus (on the Solemnity of the Holy Trinity):

It has been awhile since we traded letters, and so I feel happy again to be in contact with your good self. Thank you for our many years of real conversation, in which we – you and I - are always at the work of words. We could say of our friendship that “in the beginning was the word” –

Throughout the course of my 43-years of Jesuit life, but more specifically at the completion of 33-years of my priestly life (on June 16th), I have helped many couples prepare for their married lives, and I have been there with them when they stood before God and the people and spoke the ancient words of Power and of Making – “I will love and honor you all the days of my life ... in good times and in bad times....”

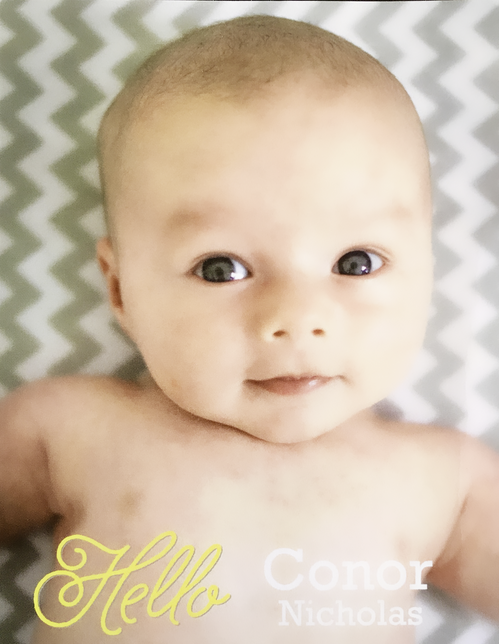

I have been aware of the birth of a second child, a boy sent to share a household with his 5-year old sister. And so, I have been thinking of his parents, whose wedding I did out in Montana in August of 2006. They sent me this photograph announcing his birth on 20 March 2017.

It has been awhile since we traded letters, and so I feel happy again to be in contact with your good self. Thank you for our many years of real conversation, in which we – you and I - are always at the work of words. We could say of our friendship that “in the beginning was the word” –

John 1:1-5 At the beginning God expressed himself. That personal expression, that word, was with God, and was God, and he existed with God from the beginning. All creation took place through him, and none took place without him. In him appeared life and this life was the light of mankind. The light still shines in the darkness and the darkness has never put it out.1

Throughout the course of my 43-years of Jesuit life, but more specifically at the completion of 33-years of my priestly life (on June 16th), I have helped many couples prepare for their married lives, and I have been there with them when they stood before God and the people and spoke the ancient words of Power and of Making – “I will love and honor you all the days of my life ... in good times and in bad times....”

I have been aware of the birth of a second child, a boy sent to share a household with his 5-year old sister. And so, I have been thinking of his parents, whose wedding I did out in Montana in August of 2006. They sent me this photograph announcing his birth on 20 March 2017.

Do you see those eyes? Do you feel the impact of ... what is it?

It is not them – the eyes - but their power of seeing. Those eyes are alive with ... not intelligence (though one might find that close to the truth), but alive with something far greater than intelligence. They are alive with real presence. They say, “I am here, and I am wondering about you who are looking at me.”

How rare is it that someone looking at us, really seeing us, actually compels us by their gaze to be more real, not hidden, to become present to the Seer. Only eyes born of God, I say, have the power to do this: “But the Lord God called to the man, and said to him, ‘Where are you?’” (Genesis 2:9)

A dear friend of mine likes to speak of the newly-born as being “fresh from God.” I love that expression, and I recognize its truth when I see Conor Nicholas holding me in his gaze. Do you notice how there is no guile in his eyes, no doubt, no suggestion of irony, no disappointment, nothing of the cool detachment one sees often in the eyes of those who wonder how others can be useful to them?

I also notice that he is not using his eyes, in order to look at an object. (This is subtle but of great importance.) Instead, his clear eyes simply see, they behold.3 Long before a child is taught who is important (and therefore worth noticing), or who is unimportant, or visually incongruent with what we like, or is a threat to us, a child just sees.

Oh to have the power again to see so freshly, to be one who sees before others have taught us how to use our eyes! I recall that beautiful lyric about a person who awakens one beautiful morning, and who, for a blessed moment, is able just to see:

Why are those beautiful eyes disconcerting? Because they reveal the soul of a new Traveler in this world who asks, “Hello. How are things out here? What will it be like to be someone like me here?” I wonder how to reply in the face of such an interrogation, because those eyes have already disarmed any capacity in me to give an answer. The eyes “ask” before the question.

What are those eyes seeing?

Rainer Maria Rilke wrote a poem, the “Archaic Torso of Apollo”, referring to a broken portion of a Greek sculpture he came to see at a museum. The moment of revelation came to him when, suddenly, he was unnerved by his awareness that this was not about him looking at an ancient sculpture, but about this work of ancient genius seeing him. The famous concluding lines are these:

When I see little Conor Nicholas gazing at me, why is it that I feel that it is he who has the advantage? The eyes seek an answer of me that I do not know how to give, because they “ask” deeper and earlier than any question. It is as if they know whether, and to what degree of truth, I am in Love, of Love, and from Love. They probe disarmingly. The only proper “answer” is to appear and to be still.

“When I say it's you I like, I'm talking about that part of you that knows that life is far more than anything you can ever see or hear or touch. That deep part of you that allows you to stand for those things without which humankind cannot survive. Love that conquers hate, peace that rises triumphant over war, and justice that proves more powerful than greed.”6

When you get a chance, Peregrinus, write to me some account of what you notice when you stand before Conor Nicholas, so fresh from God. OK?

I am your good, and old, friend in Christ, Rick, SJ

6 From “Mister Rogers” of the TV series “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” on Public Television from 1968- 2001, whose real name was Fred McFeely Rogers (1928-2003).

It is not them – the eyes - but their power of seeing. Those eyes are alive with ... not intelligence (though one might find that close to the truth), but alive with something far greater than intelligence. They are alive with real presence. They say, “I am here, and I am wondering about you who are looking at me.”

LORD, you have probed me, you know me:

2 you know when I sit and stand;

you understand my thoughts from afar.2

2 you know when I sit and stand;

you understand my thoughts from afar.2

How rare is it that someone looking at us, really seeing us, actually compels us by their gaze to be more real, not hidden, to become present to the Seer. Only eyes born of God, I say, have the power to do this: “But the Lord God called to the man, and said to him, ‘Where are you?’” (Genesis 2:9)

A dear friend of mine likes to speak of the newly-born as being “fresh from God.” I love that expression, and I recognize its truth when I see Conor Nicholas holding me in his gaze. Do you notice how there is no guile in his eyes, no doubt, no suggestion of irony, no disappointment, nothing of the cool detachment one sees often in the eyes of those who wonder how others can be useful to them?

I also notice that he is not using his eyes, in order to look at an object. (This is subtle but of great importance.) Instead, his clear eyes simply see, they behold.3 Long before a child is taught who is important (and therefore worth noticing), or who is unimportant, or visually incongruent with what we like, or is a threat to us, a child just sees.

Oh to have the power again to see so freshly, to be one who sees before others have taught us how to use our eyes! I recall that beautiful lyric about a person who awakens one beautiful morning, and who, for a blessed moment, is able just to see:

Morning has broken like the first morning,

Blackbird has spoken like the first bird.

Praise for the singing!

Praise for the morning!

Praise for them springing fresh from the world!4

Blackbird has spoken like the first bird.

Praise for the singing!

Praise for the morning!

Praise for them springing fresh from the world!4

Why are those beautiful eyes disconcerting? Because they reveal the soul of a new Traveler in this world who asks, “Hello. How are things out here? What will it be like to be someone like me here?” I wonder how to reply in the face of such an interrogation, because those eyes have already disarmed any capacity in me to give an answer. The eyes “ask” before the question.

What are those eyes seeing?

Rainer Maria Rilke wrote a poem, the “Archaic Torso of Apollo”, referring to a broken portion of a Greek sculpture he came to see at a museum. The moment of revelation came to him when, suddenly, he was unnerved by his awareness that this was not about him looking at an ancient sculpture, but about this work of ancient genius seeing him. The famous concluding lines are these:

for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.5

that does not see you. You must change your life.5

When I see little Conor Nicholas gazing at me, why is it that I feel that it is he who has the advantage? The eyes seek an answer of me that I do not know how to give, because they “ask” deeper and earlier than any question. It is as if they know whether, and to what degree of truth, I am in Love, of Love, and from Love. They probe disarmingly. The only proper “answer” is to appear and to be still.

“When I say it's you I like, I'm talking about that part of you that knows that life is far more than anything you can ever see or hear or touch. That deep part of you that allows you to stand for those things without which humankind cannot survive. Love that conquers hate, peace that rises triumphant over war, and justice that proves more powerful than greed.”6

When you get a chance, Peregrinus, write to me some account of what you notice when you stand before Conor Nicholas, so fresh from God. OK?

I am your good, and old, friend in Christ, Rick, SJ

6 From “Mister Rogers” of the TV series “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” on Public Television from 1968- 2001, whose real name was Fred McFeely Rogers (1928-2003).

Notes

[1] Translated by J.B. Phillips.

[2] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Ps 139:1–2.

[3] This very old English verb (c. 825 CE) is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary, in its earliest meaning, “To hold by, keep hold of, retain.” By the year 971 CE, it also meant, “To hold or keep in view, to watch; to regard or contemplate with the eyes; to look upon, look at (implying active voluntary exercise of the faculty of vision).”

[4] Wikipedia notes: “Morning Has Broken is a popular and well-known Christian hymn first published in 1931. It has words by English author Eleanor Farjeon and is set to a traditional Scottish Gaelic tune known as ‘Bunessan’ (it shares this tune with the 19th century Christmas Carol ‘Child in the Manger’). It is often sung in children's services. English pop musician and folk singer Cat Stevens included a version on his 1971 album Teaser and the Firecat. The song became identified with Stevens when it reached number six on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100, number one on the U.S. Easy Listening Chart in 1972, and number four on the Canadian RPM Magazine charts.”

[5] Rainer Maria Rilke, “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” translated from the German by Stephen Mitchell.

[2] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Ps 139:1–2.

[3] This very old English verb (c. 825 CE) is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary, in its earliest meaning, “To hold by, keep hold of, retain.” By the year 971 CE, it also meant, “To hold or keep in view, to watch; to regard or contemplate with the eyes; to look upon, look at (implying active voluntary exercise of the faculty of vision).”

[4] Wikipedia notes: “Morning Has Broken is a popular and well-known Christian hymn first published in 1931. It has words by English author Eleanor Farjeon and is set to a traditional Scottish Gaelic tune known as ‘Bunessan’ (it shares this tune with the 19th century Christmas Carol ‘Child in the Manger’). It is often sung in children's services. English pop musician and folk singer Cat Stevens included a version on his 1971 album Teaser and the Firecat. The song became identified with Stevens when it reached number six on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100, number one on the U.S. Easy Listening Chart in 1972, and number four on the Canadian RPM Magazine charts.”

[5] Rainer Maria Rilke, “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” translated from the German by Stephen Mitchell.

Recent

Categories

Tags

Archive

2026

2025

January

March

June

October

2024

January

March

September

October

2023

March

November

2022

2021

2020

No Comments