Letters to Peregrinus #45 - Of Storms, Inner and Outer

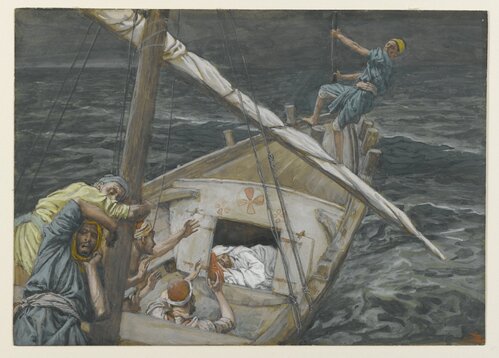

Jesus Sleeping During the Tempest (Jésus dormant pendant la tempête)

by James Tissot (French, 1836-1902)

by James Tissot (French, 1836-1902)

Dear Peregrinus (First Week of Advent)[1]:

Thank you for your call on Thanksgiving day, and now happy Advent. Your words always fly, like a dart in the hand of an “archer”,[2] quickly and smoothly towards the place within me where insight happens. You are amazing to me in this way. Wise. Sometimes intimidating. Playful. My trusted Friend.

Since very long ago, perhaps even before I entered the Jesuit Order at 19-years old (old!), I have felt the riddle of Mark 4:38 – the sleeping of Christ when His disciples, a few of them master boatmen, felt carried beyond their seafaring competence by a storm too violent.[3] Mark 4: 37 A violent squall[4] came up and waves were breaking over the boat, so that it was already filling up.[5] I imagined how scared such fishermen must have been. And why not? It intrigued me that the disciples turned (for help?) to a man whom they knew was a carpenter’s son – no mariner for sure and so not likely to be of much help to them with the boat. Jesus, to their surprise (irritation?) turned out to be serenely asleep. Something has always seemed to me so puzzling about this scene.

But this time around I noticed for the first time this: Mark 4: 38 They woke him and said to him, “Teacher, do you not care (οὐ μέλει σοι) that we are perishing?”[6] The fishermen, at least a few of them, were not scared … they were angry – “Do You not care?” This startled me. I had thought that they were afraid, and I had assumed that I knew why – “We are perishing!”

Thank you for your call on Thanksgiving day, and now happy Advent. Your words always fly, like a dart in the hand of an “archer”,[2] quickly and smoothly towards the place within me where insight happens. You are amazing to me in this way. Wise. Sometimes intimidating. Playful. My trusted Friend.

Since very long ago, perhaps even before I entered the Jesuit Order at 19-years old (old!), I have felt the riddle of Mark 4:38 – the sleeping of Christ when His disciples, a few of them master boatmen, felt carried beyond their seafaring competence by a storm too violent.[3] Mark 4: 37 A violent squall[4] came up and waves were breaking over the boat, so that it was already filling up.[5] I imagined how scared such fishermen must have been. And why not? It intrigued me that the disciples turned (for help?) to a man whom they knew was a carpenter’s son – no mariner for sure and so not likely to be of much help to them with the boat. Jesus, to their surprise (irritation?) turned out to be serenely asleep. Something has always seemed to me so puzzling about this scene.

But this time around I noticed for the first time this: Mark 4: 38 They woke him and said to him, “Teacher, do you not care (οὐ μέλει σοι) that we are perishing?”[6] The fishermen, at least a few of them, were not scared … they were angry – “Do You not care?” This startled me. I had thought that they were afraid, and I had assumed that I knew why – “We are perishing!”

Two Kinds of Anger

But then I thought more about this. The disciples (some of them?) were angry with Jesus, the God-Man, because He was with them, not because He was absent. If Jesus had not been with them, if they had concluded that God was absent and they were on their own, then fear would have been their most vividly-felt emotion, not anger.

It has made me wonder if the anger that any of us can feel towards God is actually a sign that God has come closer to us than we guess is the case. What if our anger at God is actually a sign that we are receiving what really we most need, and to be honest, what most we want: to have God be with us in our suffering. We want God to be for us according to one of our most precious names for Him – “God [is] with us”.

What is the anger of those disciples who shouted at Jesus, and why do they express it there to the God-Man?

I argue that there is “faithful” anger and “unfaithful” anger. The latter is an anger ablaze with ego and at the service of a damnable false-self that refuses to die. The former maintains the “I and Thou”: “do You not care [for me, for us]?” Unfaithful anger blames God (the accusatory finger pointing one way); faithful anger demands that God rouse Himself, be His best self and care for whom and for what we know that He cares about. We, as does the Psalmist, remind God (!) of His finest qualities, encouraging and sometimes demanding that God remember Who He is, and to act accordingly. Audacity![8]

Psalm 44 –

But I was still not satisfied that I had understood the “faithful” anger expressed to Jesus in the disciples question - “Do You not care?” I could not get out of my head that God was so near to them in that boat. God’s presence to us, as experienced, is powerful, changes how we feel and think about everything. The disciples, His own, in that boat were “covered”[10] with the divine presence. How could their anger bloom in such a circumstance?

And so I thought about those doughty[11] disciples and have concluded that they were not so much angry as fearful at the probability of their watery death. What angered them had to do with what their death would mean to those whom they loved and who depended on them. (God’s felt presence always makes us more aware of those whom we love, and less aware of ourselves no matter how challenging our circumstances.)

Each disciple out there might have been intensely aware, say, of his spouse and of his children, and how they would be damaged by the death of the man whom they counted on: a husband, a “bread-winner”, a dad, a sibling, a faithful friend. Because God was close to them that day in the storm-buffeted[12] boat, I sense that the disciples’ anger revealed a love that they had, and were feeling, for those who were precious to them – “Do You not care … about all of those people I love and who depend on me?”

Jesus would have been so proud to see such anger in each of them, because He would have seen how much they had learned from Him.

It has made me wonder if the anger that any of us can feel towards God is actually a sign that God has come closer to us than we guess is the case. What if our anger at God is actually a sign that we are receiving what really we most need, and to be honest, what most we want: to have God be with us in our suffering. We want God to be for us according to one of our most precious names for Him – “God [is] with us”.

22 All this took place to fulfill what the Lord had said through the prophet:

23 *k “Behold, the virgin shall be with child and bear a son,

and they shall name him Emmanuel,”

and they shall name him Emmanuel,”

which means “God is with us.”[7]

What is the anger of those disciples who shouted at Jesus, and why do they express it there to the God-Man?

I argue that there is “faithful” anger and “unfaithful” anger. The latter is an anger ablaze with ego and at the service of a damnable false-self that refuses to die. The former maintains the “I and Thou”: “do You not care [for me, for us]?” Unfaithful anger blames God (the accusatory finger pointing one way); faithful anger demands that God rouse Himself, be His best self and care for whom and for what we know that He cares about. We, as does the Psalmist, remind God (!) of His finest qualities, encouraging and sometimes demanding that God remember Who He is, and to act accordingly. Audacity![8]

Psalm 44 –

24 Awake! Why do you sleep, O Lord?

Rise up! Do not reject us forever!n

25 Why do you hide your face;o

why forget our pain and misery? [9]

But I was still not satisfied that I had understood the “faithful” anger expressed to Jesus in the disciples question - “Do You not care?” I could not get out of my head that God was so near to them in that boat. God’s presence to us, as experienced, is powerful, changes how we feel and think about everything. The disciples, His own, in that boat were “covered”[10] with the divine presence. How could their anger bloom in such a circumstance?

And so I thought about those doughty[11] disciples and have concluded that they were not so much angry as fearful at the probability of their watery death. What angered them had to do with what their death would mean to those whom they loved and who depended on them. (God’s felt presence always makes us more aware of those whom we love, and less aware of ourselves no matter how challenging our circumstances.)

Each disciple out there might have been intensely aware, say, of his spouse and of his children, and how they would be damaged by the death of the man whom they counted on: a husband, a “bread-winner”, a dad, a sibling, a faithful friend. Because God was close to them that day in the storm-buffeted[12] boat, I sense that the disciples’ anger revealed a love that they had, and were feeling, for those who were precious to them – “Do You not care … about all of those people I love and who depend on me?”

Jesus would have been so proud to see such anger in each of them, because He would have seen how much they had learned from Him.

Jesus Sleeps

But why is Jesus, the God-Man, sleeping?

Take a look with me at Tissot’s painting. Do you notice how tame the sea looks? It does not appear at all like “a violent squall”. The spacing between the waves is too short for the sea to be much more than “choppy”. And the door to the small cabin that Jesus has turned into His sleeping quarters is wide open. If the boat were taking on water – Mark 4: 37 and waves were breaking over the boat, so that it was already filling up.[13] – then Jesus would have been quickly doused and startled into wakefulness. It is possible that Tissot has painted a moment when the squall was just starting to develop, but then that would not explain why those disciples are so agitated and why two of them are clinging so tightly to the mast. We clearly see that three of the disciples (possibly the disciples who were not fishermen) have left off the work of helping those who were sailing the boat. These disciples, we imagine, should have been helping bale[14] the boat at the least. But, no. They have lost confidence in their ability to pitch in and help to save the boat. They have given up. See them there, turning their frightened, and unhelpful, hands towards their sleeping Lord. Puzzling isn’t it? Tissot’s contemplation deepens the riddle of this scene.

What are we to make of this, Peregrinus? I have two thoughts, and then I will close this letter.

The first concerns the contrast Tissot gets us to consider between, on the one hand, the roiled[15] but not particularly scary sea, and, on the other hand, the apparent agitation that we see overcoming the disciples. The terror blazes in the disciples at the mast and in the one at the rudder. (We cannot see the emotion of the three disciples reaching out to Jesus – the ones who are angry?) Their reaction is out of proportion to what the sea is bringing against their boat.

This is a clue; an important spiritual perception. Whenever something is going on in a person’s life, and his or her reaction to it is out of proportion to what actually is happening, we may rightly conclude that this person is being assailed by a temptation. (In the biblical language, this person is being assailed by a demon[16] or demons.) Something is scaring him or her, something is there that we cannot see. But they sense its presence, and they are reacting to it. What was it? In this case, the Sea of Galilee is disturbed, while the disciples in the boat are greatly disturbed. Something is going on here, and I think that Tissot is onto it. The “violent squall” is greater within the disciples than it actually is outside of them.

A couple of years ago a biblical scholar helped me understand that this Storm at Sea passage (Mark 4:35-41) is best interpreted in Mark’s Gospel not by what comes before it in Chapter 4 but by what comes immediately after it: the encounter with “the Legion” (i.e., the one hundred demons) possessing the man of Gerasa[17] (Mark 5:1-20). He explained to me that the “violent squall” was to be understood as the Legion calling on the Sea, the mythological adversary of Yahweh,[18] to stop, to repulse Jesus the God-Man from reaching that shore. The Legion sensed a Presence approaching on the sea that was enormously dangerous to them. Therefore, the Sea of Galilee had risen up at the command of the demons, in order to keep Jesus from ever getting to that shore. This would explain why it was that the disciples in the boat were terrified (I am not here contradicting what I said earlier that at least some of them were angry.) The disciples sensed the spiritual malevolence[19] in the squall and were reacting to that. Jesus, then, peacefully slept because no such spiritual menace could get to Him. Notice that when Jesus is woken up, he does not scold them about not helping each other with the boat – the practical effort of “all hands on deck”. Rather He warns them about their lack of faith. He had quickly perceived a spiritual menace stalking them all, coming at them from the opposite shore, moving against them in a way more dangerous than a stormy sea.

My second thought is this. I believe that Jesus, a landlubber[21] more acquainted with sawhorses than sails, trusted his fishermen disciples. That was their “home field” since their youth, having been taught by their fathers all of the ways and moods of the Sea of Galilee. Jesus could sleep because He trusted them, could let go His long day, and entrust safe passage across the sea to his friends. I have perceived the feelings of a parent when his or her little one has fallen asleep on his or her watch. The parent knows that the little one is not afraid, who can fall peacefully into slumber, because his or her parent stands guard. Psalm 121 - 4 Behold, the guardian of Israel never slumbers nor sleeps.[22] It must have pleased Jesus very much, Who was often needing to be strong and competent, to let His closest friends be strong and competent instead of Him, wanting them to be in their own powers and competencies … and to let Himself be watched over by them. Remember “the little Lord Jesus / asleep on the hay”?

Perhaps, then, we should consider more than we do that God trusts us, and that it pleases Him to do so.

Take a look with me at Tissot’s painting. Do you notice how tame the sea looks? It does not appear at all like “a violent squall”. The spacing between the waves is too short for the sea to be much more than “choppy”. And the door to the small cabin that Jesus has turned into His sleeping quarters is wide open. If the boat were taking on water – Mark 4: 37 and waves were breaking over the boat, so that it was already filling up.[13] – then Jesus would have been quickly doused and startled into wakefulness. It is possible that Tissot has painted a moment when the squall was just starting to develop, but then that would not explain why those disciples are so agitated and why two of them are clinging so tightly to the mast. We clearly see that three of the disciples (possibly the disciples who were not fishermen) have left off the work of helping those who were sailing the boat. These disciples, we imagine, should have been helping bale[14] the boat at the least. But, no. They have lost confidence in their ability to pitch in and help to save the boat. They have given up. See them there, turning their frightened, and unhelpful, hands towards their sleeping Lord. Puzzling isn’t it? Tissot’s contemplation deepens the riddle of this scene.

What are we to make of this, Peregrinus? I have two thoughts, and then I will close this letter.

The first concerns the contrast Tissot gets us to consider between, on the one hand, the roiled[15] but not particularly scary sea, and, on the other hand, the apparent agitation that we see overcoming the disciples. The terror blazes in the disciples at the mast and in the one at the rudder. (We cannot see the emotion of the three disciples reaching out to Jesus – the ones who are angry?) Their reaction is out of proportion to what the sea is bringing against their boat.

This is a clue; an important spiritual perception. Whenever something is going on in a person’s life, and his or her reaction to it is out of proportion to what actually is happening, we may rightly conclude that this person is being assailed by a temptation. (In the biblical language, this person is being assailed by a demon[16] or demons.) Something is scaring him or her, something is there that we cannot see. But they sense its presence, and they are reacting to it. What was it? In this case, the Sea of Galilee is disturbed, while the disciples in the boat are greatly disturbed. Something is going on here, and I think that Tissot is onto it. The “violent squall” is greater within the disciples than it actually is outside of them.

A couple of years ago a biblical scholar helped me understand that this Storm at Sea passage (Mark 4:35-41) is best interpreted in Mark’s Gospel not by what comes before it in Chapter 4 but by what comes immediately after it: the encounter with “the Legion” (i.e., the one hundred demons) possessing the man of Gerasa[17] (Mark 5:1-20). He explained to me that the “violent squall” was to be understood as the Legion calling on the Sea, the mythological adversary of Yahweh,[18] to stop, to repulse Jesus the God-Man from reaching that shore. The Legion sensed a Presence approaching on the sea that was enormously dangerous to them. Therefore, the Sea of Galilee had risen up at the command of the demons, in order to keep Jesus from ever getting to that shore. This would explain why it was that the disciples in the boat were terrified (I am not here contradicting what I said earlier that at least some of them were angry.) The disciples sensed the spiritual malevolence[19] in the squall and were reacting to that. Jesus, then, peacefully slept because no such spiritual menace could get to Him. Notice that when Jesus is woken up, he does not scold them about not helping each other with the boat – the practical effort of “all hands on deck”. Rather He warns them about their lack of faith. He had quickly perceived a spiritual menace stalking them all, coming at them from the opposite shore, moving against them in a way more dangerous than a stormy sea.

Be near me, Lord Jesus

I ask Thee to stay

Close by me forever

And love me, I pray[20]

I ask Thee to stay

Close by me forever

And love me, I pray[20]

My second thought is this. I believe that Jesus, a landlubber[21] more acquainted with sawhorses than sails, trusted his fishermen disciples. That was their “home field” since their youth, having been taught by their fathers all of the ways and moods of the Sea of Galilee. Jesus could sleep because He trusted them, could let go His long day, and entrust safe passage across the sea to his friends. I have perceived the feelings of a parent when his or her little one has fallen asleep on his or her watch. The parent knows that the little one is not afraid, who can fall peacefully into slumber, because his or her parent stands guard. Psalm 121 - 4 Behold, the guardian of Israel never slumbers nor sleeps.[22] It must have pleased Jesus very much, Who was often needing to be strong and competent, to let His closest friends be strong and competent instead of Him, wanting them to be in their own powers and competencies … and to let Himself be watched over by them. Remember “the little Lord Jesus / asleep on the hay”?

Perhaps, then, we should consider more than we do that God trusts us, and that it pleases Him to do so.

Concluding Thought

Why have I chosen this particular biblical scene as one suitable for the First Week of Advent? I say this. I have sensed these days the “roiling” happening within very many people that I know, of all ages. Many recognize a Storm is raging in American culture and politics and religions, in the vexations of bad habits like “OK, Boomer”, and in the souls of otherwise strong and steady people.

I have wondered how we too quickly externalize the Storm, blaming it on American culture, on politicians, on religious leaders, and we miss the danger of a temptation assailing[23] us internally. (Jesus saw the stormy sea, but He sensed instantly the greater “storm” raging inside of his disciples.)

In this holy season of Advent, we could hardly do better than to let the Lord Christ come to dwell within us, to welcome Him there, and there, within, when the Storm has gained access and overthrown our peace, to watch Him rise up and hear Him say, “Quiet! Be still!”

Thank you for everything, old friend,

Love,

Rick

I have wondered how we too quickly externalize the Storm, blaming it on American culture, on politicians, on religious leaders, and we miss the danger of a temptation assailing[23] us internally. (Jesus saw the stormy sea, but He sensed instantly the greater “storm” raging inside of his disciples.)

In this holy season of Advent, we could hardly do better than to let the Lord Christ come to dwell within us, to welcome Him there, and there, within, when the Storm has gained access and overthrown our peace, to watch Him rise up and hear Him say, “Quiet! Be still!”

Mark 4: 39 He woke up, rebuked the wind, and said to the sea, “Quiet! Be still!”* The wind ceased and there was great calm. 40 Then he asked them, “Why are you terrified? Do you not yet have faith?” 41 *n They were filled with great awe and said to one another, “Who then is this whom even wind and sea obey?” [24]

Thank you for everything, old friend,

Love,

Rick

Notes

[1] See https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/4492. James Tissot (French, 1836-1902). Jesus Sleeping During the Tempest (Jésus dormant pendant la tempête) on Mark 4:35-41, 1886-1896. Opaque watercolor over graphite on gray wove paper, Image: 5 1/2 x 7 11/16 in. (14 x 19.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Purchased by public subscription, 00.159.101 (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 00.159.101_PS2.jpg).

[2] I learned on the Darts 501 website that the term “Archer” is a slang term in professional Darts: “Refers to a Player who throws very quick smooth darts, like an archer’s arrow (also known as a “Derek”).” I further learned that an “Archer” contrasts with a Player called a “Chucker” who just “‘chucks’ the darts at the board, who doesn’t aim or care.”

[3] I learned that the Sea of Galilee is consistently deep enough to scare anyone, especially when its rage was catalyzed by a violent wind roaring down out of the North: “Its area is 166.7 km2 (64.4 sq mi) at its fullest, and its maximum depth is approximately 43 m (141 feet). The lake is fed partly by underground springs, although its main source is the Jordan River, which flows through it from north to south.”

[4] The Oxford English Dictionary at the noun “squall”. It is fascinating to discover that the original use of this noun, attested in 1570, meant: “A small or insignificant person. Usually as a term of abuse.” Perhaps this explains how this noun came to mean by 1709: “The action or habit of squalling or talking in a shrill voice”. We notice how people who are judged “small or insignificant” by others can end up asserting themselves in over-loud ways, earning them from others an abusive description. (Danny DeVito and Joe Pesci have made their acting careers working this trope.) It is therefore more richly descriptive to speak of a storm as a “squall”, in which the violent noise of the storm is what is most upsetting or terrifying to those caught in it. I recall how often I have heard people describe a hurricane or tornado not so much by what it looked like to them (the only thing that comes through to us watching the News) but by what it sounded like to them: “It sounded like an enormous train barreling down on us,” etc.

[5] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Mk 4:37.

[6] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Mk 4:38.

* God is with us: God’s promise of deliverance to Judah in Isaiah’s time is seen by Matthew as fulfilled in the birth of Jesus, in whom God is with his people. The name Emmanuel is alluded to at the end of the gospel where the risen Jesus assures his disciples of his continued presence, “… I am with you always, until the end of the age” (Mt 28:20).

k Is 7:14 LXX

[7] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Mt 1:22–23.

[8] The Oxford English Dictionary at the mid-15th century noun “audacity” – “Boldness, daring, intrepidity; confidence.”

n Ps 10:1; 74:1; 77:8; 79:5; 83:2

o Ps 10:11; 89:47; Jb 13:24

[9] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Ps 44:24–25.

[10] I used this word “covered” in acknowledgment of a couple of holy friends of mine who like to use this expression, praying that my life be “covered” by their prayers for me. I am not sure where this language originates, or perhaps am not even sure what it means … though I know they mean this in a very good way. But the way I decided to take it is in accord with Genesis 3:21 - 21 The Lord God made for the man and his wife garments of skin, with which he clothed them.” To be “covered” by another’s prayers for me will mean this: their prayers are an image of God Who saw how afraid his children were of the “outside” (beyond the Garden of God), and Who then sat down at His sewing machine and by hand constructed outfits that perfectly fit his Adam and Eve. They were “covered”.

[11] The Oxford English Dictionary at the adjective “doughty” – “Of a person: possessing courage and determination; brave, bold, resolute. In early use also as a general term of approbation: †good, worthy, noble (obsolete).”

[12] The Oxford English Dictionary at the verb “to buffet” – “To beat back, contend with (waves, etc.).”

[13] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Mk 4:37.

[14] The Oxford English Dictionary concerning the verb “to bale” – “To lade or throw water out of a boat or ship with buckets (formerly called bails) or other vessels. Const. to bale the water out, bale the boat (out). to bale up: to scoop up.”

[15] The Oxford English Dictionary at the 14th century verb “to roil” – “To play boisterously, to frolic, romp about, esp. in a rough manner; to fidget.”

[16] The New Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible – “The Greek daimonion (“demon”) comes from the adjective daimonios (δαιμόνιος, “divine”). Related terms include daimōn (divinity, a god, goddess) or pneuma (πνεῦμα, spirit). Generally, a demon is a preternatural semi-divine entity, from the ambiguous root daiō (δαίω, tear apart, divide,” or, perhaps, “apportion or burn”). Although indeterminate in the OT, demons in the NT are seen as evil or unclean spiritual beings with the capacity to harm life or allure people to heresy or immorality.”

[17] In the New Interpreters Dictionary of the Bible – “Gerasa (Jerash) is one of the three names given in manuscripts of the NT to the town in which Jesus met two people (one in Mark) possessed by demons. He exorcised the demons, sending them into a herd of pigs that rushed off the side of a cliff into the Sea of Galilee (Matt 8:28–34; Mark 5:1–17; Luke 8:26–39).”

[18] The New Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible – “At the appearance of Yahweh, the sea retreats (Ps 114:3), and Yahweh defeats the sea (Job 26:12–14; Isa 51:9–10), treading on it as a victor would trample his enemies (Job 9:8). Having defeated the sea, like Marduk in Enuma elish, Yahweh then creates the world (Pss 74:13–17; 89:9–12 [Heb. 89:10–13]). The primeval waters of chaos were symbolically represented in the Temple by the enormous “molten sea” (1 Kgs 7:23–26) in the Temple courtyard.”

[19] The Oxford English Dictionary at the noun “malevolent”, when used as an adjective to describe a person: “Of a person, feeling, or action: desirous of evil to others; entertaining, actuated by, or indicative of ill will; disposed or addicted to ill will.”

[20] From the Christmas carol, “Away in the Manger.”

[21] The Oxford English Dictionary at the noun “landlubber” – “A sailor's term of contempt for a landsman.”

[22] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Ps 121:4.

[23] The Oxford English Dictionary at the verb “to assail” – “To harass, incite, or lure with temptation; to tempt, to try.”

* Quiet! Be still!: as in the case of silencing a demon (Mk 1:25), Jesus rebukes the wind and subdues the turbulence of the sea by a mere word; see note on Mt 8:26.

* Jesus is here depicted as exercising power over wind and sea. In the Christian community this event was seen as a sign of Jesus’ saving presence amid persecutions that threatened its existence.

n 1:27.

[24] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Mk 4:39–41.

[2] I learned on the Darts 501 website that the term “Archer” is a slang term in professional Darts: “Refers to a Player who throws very quick smooth darts, like an archer’s arrow (also known as a “Derek”).” I further learned that an “Archer” contrasts with a Player called a “Chucker” who just “‘chucks’ the darts at the board, who doesn’t aim or care.”

[3] I learned that the Sea of Galilee is consistently deep enough to scare anyone, especially when its rage was catalyzed by a violent wind roaring down out of the North: “Its area is 166.7 km2 (64.4 sq mi) at its fullest, and its maximum depth is approximately 43 m (141 feet). The lake is fed partly by underground springs, although its main source is the Jordan River, which flows through it from north to south.”

[4] The Oxford English Dictionary at the noun “squall”. It is fascinating to discover that the original use of this noun, attested in 1570, meant: “A small or insignificant person. Usually as a term of abuse.” Perhaps this explains how this noun came to mean by 1709: “The action or habit of squalling or talking in a shrill voice”. We notice how people who are judged “small or insignificant” by others can end up asserting themselves in over-loud ways, earning them from others an abusive description. (Danny DeVito and Joe Pesci have made their acting careers working this trope.) It is therefore more richly descriptive to speak of a storm as a “squall”, in which the violent noise of the storm is what is most upsetting or terrifying to those caught in it. I recall how often I have heard people describe a hurricane or tornado not so much by what it looked like to them (the only thing that comes through to us watching the News) but by what it sounded like to them: “It sounded like an enormous train barreling down on us,” etc.

[5] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Mk 4:37.

[6] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Mk 4:38.

* God is with us: God’s promise of deliverance to Judah in Isaiah’s time is seen by Matthew as fulfilled in the birth of Jesus, in whom God is with his people. The name Emmanuel is alluded to at the end of the gospel where the risen Jesus assures his disciples of his continued presence, “… I am with you always, until the end of the age” (Mt 28:20).

k Is 7:14 LXX

[7] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Mt 1:22–23.

[8] The Oxford English Dictionary at the mid-15th century noun “audacity” – “Boldness, daring, intrepidity; confidence.”

n Ps 10:1; 74:1; 77:8; 79:5; 83:2

o Ps 10:11; 89:47; Jb 13:24

[9] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Ps 44:24–25.

[10] I used this word “covered” in acknowledgment of a couple of holy friends of mine who like to use this expression, praying that my life be “covered” by their prayers for me. I am not sure where this language originates, or perhaps am not even sure what it means … though I know they mean this in a very good way. But the way I decided to take it is in accord with Genesis 3:21 - 21 The Lord God made for the man and his wife garments of skin, with which he clothed them.” To be “covered” by another’s prayers for me will mean this: their prayers are an image of God Who saw how afraid his children were of the “outside” (beyond the Garden of God), and Who then sat down at His sewing machine and by hand constructed outfits that perfectly fit his Adam and Eve. They were “covered”.

[11] The Oxford English Dictionary at the adjective “doughty” – “Of a person: possessing courage and determination; brave, bold, resolute. In early use also as a general term of approbation: †good, worthy, noble (obsolete).”

[12] The Oxford English Dictionary at the verb “to buffet” – “To beat back, contend with (waves, etc.).”

[13] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Mk 4:37.

[14] The Oxford English Dictionary concerning the verb “to bale” – “To lade or throw water out of a boat or ship with buckets (formerly called bails) or other vessels. Const. to bale the water out, bale the boat (out). to bale up: to scoop up.”

[15] The Oxford English Dictionary at the 14th century verb “to roil” – “To play boisterously, to frolic, romp about, esp. in a rough manner; to fidget.”

[16] The New Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible – “The Greek daimonion (“demon”) comes from the adjective daimonios (δαιμόνιος, “divine”). Related terms include daimōn (divinity, a god, goddess) or pneuma (πνεῦμα, spirit). Generally, a demon is a preternatural semi-divine entity, from the ambiguous root daiō (δαίω, tear apart, divide,” or, perhaps, “apportion or burn”). Although indeterminate in the OT, demons in the NT are seen as evil or unclean spiritual beings with the capacity to harm life or allure people to heresy or immorality.”

[17] In the New Interpreters Dictionary of the Bible – “Gerasa (Jerash) is one of the three names given in manuscripts of the NT to the town in which Jesus met two people (one in Mark) possessed by demons. He exorcised the demons, sending them into a herd of pigs that rushed off the side of a cliff into the Sea of Galilee (Matt 8:28–34; Mark 5:1–17; Luke 8:26–39).”

[18] The New Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible – “At the appearance of Yahweh, the sea retreats (Ps 114:3), and Yahweh defeats the sea (Job 26:12–14; Isa 51:9–10), treading on it as a victor would trample his enemies (Job 9:8). Having defeated the sea, like Marduk in Enuma elish, Yahweh then creates the world (Pss 74:13–17; 89:9–12 [Heb. 89:10–13]). The primeval waters of chaos were symbolically represented in the Temple by the enormous “molten sea” (1 Kgs 7:23–26) in the Temple courtyard.”

[19] The Oxford English Dictionary at the noun “malevolent”, when used as an adjective to describe a person: “Of a person, feeling, or action: desirous of evil to others; entertaining, actuated by, or indicative of ill will; disposed or addicted to ill will.”

[20] From the Christmas carol, “Away in the Manger.”

[21] The Oxford English Dictionary at the noun “landlubber” – “A sailor's term of contempt for a landsman.”

[22] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Ps 121:4.

[23] The Oxford English Dictionary at the verb “to assail” – “To harass, incite, or lure with temptation; to tempt, to try.”

* Quiet! Be still!: as in the case of silencing a demon (Mk 1:25), Jesus rebukes the wind and subdues the turbulence of the sea by a mere word; see note on Mt 8:26.

* Jesus is here depicted as exercising power over wind and sea. In the Christian community this event was seen as a sign of Jesus’ saving presence amid persecutions that threatened its existence.

n 1:27.

[24] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Mk 4:39–41.

Recent

Categories

Tags

Archive

2026

2025

January

March

June

October

2024

January

March

September

October

2023

March

November

2022

2021

2020

No Comments